Talk For Mycoverse, Forest Grandfathers: Russian Mushroom Wisdom And The Ancient Art Of Listening

In the shadowed depths of Russian forests, where mist weaves between ancient birch and pine, lives a figure both humble and profound—the Старичок-Боровичок, the Little Old Mushroom Man. Standing just two inches tall with a gray beard and a mushroom cap crown, this forest grandfather embodies thousands of years of Slavic wisdom about the delicate relationship between humans and the natural world. Far from mere folklore, these woodland spirits represent a sophisticated understanding of forest ecology, moral reciprocity, and the transformative power of respecting nature's hidden laws.

Photo by Jesse Bauer on Unsplash

Join upcoming events on Eventbrite

〰️

Join upcoming events on Eventbrite 〰️

This ancient wisdom calls to us across centuries, finding new expression in unexpected places. Growing up in Vladivostok—Russia's far eastern port city near the Chinese and North Korean borders—with Armenian-Russian heritage, I inhabited a unique position between two cultures: complete in neither but able to observe both. The contrast was striking: during Vladivostok's severe winters and long cold seasons, kids often got sick, and suitcases of delicious delicacies, fruits, dried fruits and spices would arrive from Yerevan, nurtured by the Mediterranean sun, instantly helping us through any cold or flu. My spicy mountain diet was balanced against cabbage, potato, and carrot soups and salads in endless combinations—two different relationships with the natural world that shaped my understanding of how geography influences culture till much later at 14, I moved to United States.

This research emerges from that liminal space and my collaboration with Mycoverse in Pasadena CA, a vibrant fungi-focused community founded by Aaron Tupac that has brought together over 1,000 myconauts across 70+ events since 2021. For the past year, I've been attending their Monday evening gatherings at Arlington Garden in Pasadena, drawn into deep reverence for the topics, people, and Aaron's masterful facilitation. In early 2025, I offered my crafting background as program support, sparking the idea for my "Mushroom Spirits" workshop. What began as exploring global fungal folklore revealed such rich Russian traditions that this entire presentation and post emerged—dedicated to the forest grandfathers and shamanic practices of Siberian territories. This is just the beginning of a mythological journey across cultures, exploring how different peoples have honored their fungal allies throughout history.

Key Threads

Key questions this article explores:

How do Slavic forest spirits embody ancient ecological wisdom and moral teaching?

What can traditional Russian mushroom culture teach us about sustainable relationships with nature?

How have political upheavals shaped the preservation and loss of indigenous knowledge systems?

Where do we find traces of shamanic traditions surviving in modern Russia and Siberia?

The Forest Grandfathers: Guardians Of Ancient Wisdom

"Grandfather Borovichok manages all the mushrooms in the forest. If a traveler is pure of soul - he will reward them with a full basket of mushrooms and berries, but if they are callous of soul, then he will make them wander lost."

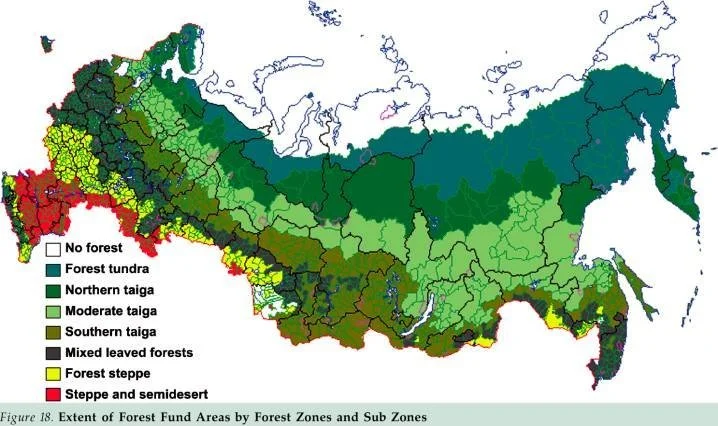

Russia's vast forest geography—covering 8.2 million square kilometers and nearly half the country's landmass—created the perfect conditions for forest spirits like the Borovichok to flourish in both ecology and imagination. The Russian taiga—boreal forests dominated by birch, pine, spruce, and fir—spans over 12 million square kilometers as Earth's largest forested region, creating an environment where fungi became central to survival, spirituality, and cultural identity. For over a thousand years, these dense woodlands served as the economic foundation of Russian life, providing primary materials for construction, fuel, and trade long before agriculture dominated the landscape. Traditional Russian peasants developed seasonal migration patterns, relocating entire families to forest camps during late summer and early fall harvesting seasons, creating deep seasonal immersion in woodland life that reinforced spiritual relationships with forest beings. The sheer geographic isolation created by Russia's expansive forests meant that remote woodland communities maintained oral traditions and pre-Christian animistic beliefs that urban areas lost to modernization, allowing ancient wisdom about reciprocal relationships with forest spirits to survive intact through centuries of political and religious change.

These forest grandfathers—appearing as tiny, gray-bearded elders wearing various mushroom caps—serve as both protectors and moral examiners in Slavic folklore. Usually invisible, they become known through their actions: reward the respectful with abundant harvests, punish the greedy with poisonous mushrooms slipped into their baskets, or lead the disrespectful deep into forest mazes where they become hopelessly lost.

The relationship is reciprocal and ritualized. Traditional mushroom gatherers would ask permission from the Borovichok before harvesting, then offer thanks afterward—recognizing that the forest's gifts come through relationship, not entitlement. This wasn't superstition but practical wisdom: those who approached the forest with respect and knowledge were more likely to identify safe, edible species and sustainable harvesting practices.

The Borovichok's preference for specific mushrooms—usually milk caps (lactarius species) and saffron milk caps (lactarius deliciosus)—reflects deep ecological knowledge. These were among the "noble three" mushrooms that sustained Russians through harsh winters for centuries: white mushrooms (porcini), milk caps, and saffron milk caps. They were prized not only for their safety (they had no dangerous lookalikes) but for their superior preservation qualities and nutritional density during Orthodox fasting periods when meat was forbidden.

Sources:

Teaching Through Enchantment: Lessons From Soviet Fairy Tales

Soviet-era animated films preserved and transformed these forest grandfather figures into powerful teaching stories that continue to resonate across generations. Two examples illuminate how these spirits operate as patient educators rather than punitive authorities.

In "The Little Pipe and the Jug" (1950), young Zhenya encounters a forest guardian who offers her a magical pipe that makes hidden strawberries visible—but only in exchange for her collecting jug. Delighted with the shortcut, she trades away her vessel, only to realize she now has no way to gather the berries she can finally see. The guardian's patient trading system creates experiential learning: he doesn't lecture about patience and preparation but allows Zhenya to discover through her own choices that "without labor and without patience, there won't be enough berries even for a saucer of jam."

More dramatically, in "Morozko" (1964), the Старичок-Боровичок transforms the arrogant Ivan into a half-man, half-bear after Ivan rudely dismisses the forest spirit's gifts and boasts of his strength while threatening wildlife. The guardian leaves a stone inscription: "If you weren't so rude, you wouldn't walk around with a bear's muzzle." Unlike gentle corrections, this forest protector delivers immediate consequences that force authentic character development—Ivan can only regain human form through genuinely selfless acts, not those performed for reward.

These stories reveal forest spirits as sophisticated moral educators who understand that lasting wisdom comes through experience rather than instruction. They create conditions where learners discover natural laws through their own choices, embodying the principle that the most profound teachers don't force understanding but patiently guide students toward their own revelations.

This trickster wisdom offers practical guidance for modern relationships: when frustrated with someone's behavior, consider the forest grandfather approach. Instead of lecturing or confronting directly, create opportunities for them to discover consequences naturally. Ask questions that lead them to their own insights. Set up situations where they experience the results of their choices firsthand. Like the patient Borovichok trading magical items back and forth, sometimes the most effective teaching happens through patient redirection rather than direct correction.

Sources:

Visual Folklore: The Language Of Mushroom Imagery

Russian visual culture reveals an obsession with mushroom imagery that extends far beyond practical foraging into realms of aesthetic delight and spiritual symbolism. Growing up in Vladivostok during the late Soviet period of the 1980s, I could see mushrooms everywhere I looked—in cartoons, books, and films. They were adorable and clearly cherished, appearing as symbols of abundance, mystery, and connection to forest magic. Yet this visual celebration existed alongside a troubling disconnect: while mushrooms dominated our cultural imagination, the practical knowledge of foraging had become dangerous territory, creating a stark contradiction between representation and lived experience.

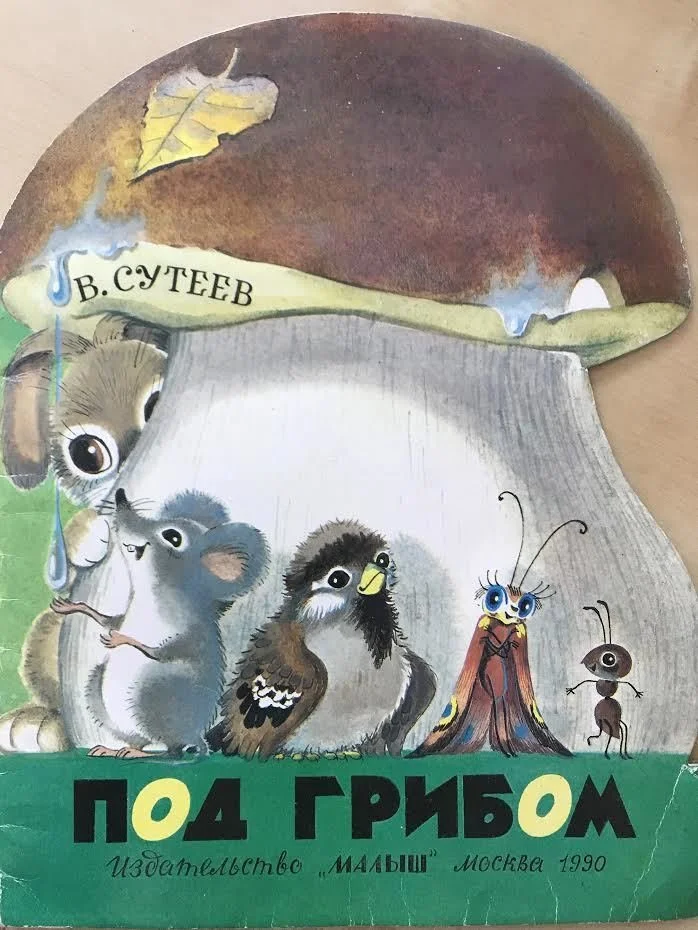

From intricate Khokhloma woodwork featuring mushroom motifs to children's illustrations of magical mushroom houses. Soviet animator Vladimir Suteev's work exemplifies this visual tradition, creating animated mushrooms that dance, shelter forest creatures, and serve as magical dwellings. His films like "Under the Mushroom" transform fungi into architectural marvels—tiny umbrellas that expand to shelter entire communities of woodland animals during rainstorms, embodying themes of hospitality, resourcefulness, and the forest's protective capacity.

The aesthetic extends into domestic life through traditional crafts: dried mushrooms strung on ropes like jewelry, decorative baskets designed specifically for mushroom gathering, and ornate serving pieces celebrating the "king of mushrooms." This visual language suggests that mushrooms occupy a special category in Russian consciousness—not merely food but symbols of wild wisdom, seasonal gifts, and the rewards that come to those who understand natural rhythms.

Ukrainian illustrator Okhrim Sudomora's "The War between Mushrooms and Beetles" (1919) reveals how mushroom imagery served political allegory during revolutionary periods. Published during the Russian Civil War, the book used forest conflicts to process human warfare, suggesting that mushroom symbolism carried enough cultural weight to serve as vehicles for complex social commentary.

Sources:

Lost Wisdom: How Politics Can Undermine Culture

Russia's sophisticated mushroom culture—built around 195 Orthodox fasting days per year when meat consumption was forbidden and families consumed over 150 kilograms of mushrooms annually as their primary protein source—represented one of history's most advanced mycological knowledge systems. Barefoot specialists worked in freezing darkness, identifying premium specimens by touch alone, while entrepreneurs invented copper-tube devices to cut large mushrooms into perfect miniatures worth ten times regular prices.

This wasn't primitive foraging but a complex economy synchronized with religious calendars and seasonal rhythms. The original "noble three" mushrooms—white mushrooms (porcini), milk caps (lactarius species), and saffron milk caps (lactarius deliciosus)—had no dangerous lookalikes, making them completely safe for widespread consumption.

Families developed sophisticated preservation techniques that sustained them through long winters. One remarkable method, preserved from Alexander Tvardovsky’s wife (a famous Soviet poet 1910-1971), demonstrates this expertise: fry mushrooms thoroughly without seasonings, pack tightly in glass jars, then cover with melted butter that hardens to create perfect preservation. This technique could keep mushrooms edible for months, providing essential protein during the harsh winter months when fresh food was scarce.

Ergot fungus on rye caused mass poisonings called "evil convulsions" - 15 epidemics in Russia from 1780-1880 alone. The poor ate contaminated bread and sought healing in monasteries, where miraculous recoveries occurred because monastery grain stores were old enough that ergot had lost its toxicity - though this wasn't understood at the time.

The Bolsheviks initially profited from this expertise, earning $480,000 annually from American mushroom exports. But collectivization—Stalin's forced agricultural policy that eliminated private farming—systematically destroyed the entire system. Soviet authorities explicitly used class language to dismantle Russia's mycological culture, dismissing artisanal varieties like premium saffron milk caps as "class-alien" while promoting mass-produced champignons as appropriately "unpretentious and cheap" for proletarian consumption.

The tragic irony was profound: foods requiring extraordinary expertise were rebranded as desperate substitutes for "proper" urban provisions. When the Soviets abolished the religious calendar framework, they accidentally severed the temporal rhythms that made such mycological mastery possible, leaving only industrial cultivation and generations of forgotten expertise.

As forests disappeared for farms and cities, Russians were forced to expand from three noble species to nearly 500 varieties today. But this expansion came with mass mushroom poisonings—a crisis that never existed when people stuck to the original three safe species. The shift from specialized knowledge to desperate foraging marked the collapse of sustainable traditions refined over centuries.

This generational break in knowledge transmission became deeply personal during my childhood in Vladivostok. Despite mushrooms being beloved in visual culture, the folk wisdom had become dangerous territory. Stories reached me through my mother and grandmother of friends getting poisoned, creating a clear message: don't touch them—this was something left only to the experts. The contrast was stark and telling: mushrooms everywhere in our cultural imagination, yet forbidden in practice due to lost traditional knowledge. This disconnect perfectly illustrates how cultural transmission fractures when political upheaval severs the patient, intergenerational transfer of practical wisdom.

Sources:

“Everyone can call on the magic powers of the web of life. You have to find it in yourself.”

Sacred Journeys: The Shamanic Revival In Modern Siberia

Despite Soviet persecution from 1920 onward, indigenous shamanic traditions survived in Siberia's most isolated regions and are now experiencing remarkable revival. Among the Khanty, Mansi, Koryak, and Chukchi peoples—indigenous groups scattered across the vast Siberian territories from the Ural Mountains to the Bering Strait—fly agaric served as sacred mediator between shamans and spirit worlds, while knowledge keepers secretly preserved practices that authorities tried to destroy through decades of underground transmission.

Archaeological evidence reveals the ancient depth of these traditions. The Pegtymel petroglyphs in Russia's far eastern territories provide stunning 2,000-year-old documentation of mushroom-human spiritual relationships. Carved high above the Pegtymel River near the East Siberian Sea, these remarkable images show "men and women with a large mushroom on their heads" and "mushroom people who have one or more mushrooms actually replacing their heads." This archaeological evidence demonstrates that the modern Chukchi shamanic practices using fly agaric have roots stretching back millennia in this exact region.

The sophistication of these traditions extended far beyond simple consumption. Koryak tribesmen dried their fly agaric over fires, often in socks, while in eastern Siberia, shamans would consume the mushrooms and others would drink the shaman's urine, which contained psychoactive elements that were often more potent than the original mushrooms with fewer negative effects. The Khanty and Koryak used Amanita muscaria not only for spiritual journeys but also for courage, anxiety reduction, and physical healing—Chukchi women ate dried mushrooms to relieve pain and muscular soreness from tanning reindeer hides.

Spiritual experiences included visions of 'mushroom-men'—small, stocky, sometimes neckless beings who moved swiftly and guided shamans on journeys to the Other-World. In Slavic connections, fly agaric was associated with Veles, the shapeshifting god of earth, waters, forests, and the underworld, who bestowed these sacred mushrooms as gifts to humans, creating reciprocal relationships where people offered the first mushroom they found back to Veles.

While European traditions often cast mushrooms as harbingers of dark sorcery—marking witch circles and devil's dances in folklore that intensified during the witch hunt periods—Slavic cultures embraced fungi as symbols of fertile abundance and protective power. Archaeological evidence supports this benevolent association: ancient Slavic stone idols carved in mushroom shapes were dedicated to deities like Veles, believed to provide fertility for both soil and people, with worshippers bringing gifts and seeking healing by sitting upon these sacred stones.

The original text mentions that mushrooms growing on house walls signaled forthcoming marriage proposals for young women, while ethnomycological research by scholars like Valeria Kolosova documents the deep connection between mushrooms and fertility symbolism in Slavic naming traditions, where certain fungi were perceived through anthropomorphic and even erotic metaphors. This association with reproductive power may stem from mushrooms' phallic appearance—Siberian Nivkh legends described them as spirits' organs emerging from the underworld, while Ket folklore told of forest phalluses that attached to women, creating the first men. Rather than representing malevolent witchcraft, these traditions positioned mushrooms as bridges between earthly and divine fertility, guardians of abundance whose mysterious overnight appearance suggested benevolent supernatural intervention in human affairs.

Today, authentic shamanic practices continue among the Khanty, while Tuva remains one of the most isolated regions where shamanism has been preserved. Cultural revival efforts include the "Yordyn Games" Spring Festival of Indigenous Peoples of Baikal, reintroduced after a 100-year break, and the Republic of Tuva's festival 'Call of 13 Shamans.'

These knowledge keepers—from barefoot mushroom specialists to Siberian shamans—understood something we're forgetting in our fast, transactional, material world: that wisdom traditions require patient cultivation across generations. They held onto practices not because they were profitable or convenient, but because they recognized their responsibility as carriers of essential knowledge.

What are you being called to hold onto today? In a world where algorithms replace intuition and efficiency trumps relationship, what ancient wisdom seeks preservation through your hands? The forest grandfathers remind us that some knowledge can only be transmitted through direct experience, patient practice, and willingness to be taught by forces greater than human convenience.

Sources:

Woven Wisdom

Truth worth holding onto:

Knowledge Keeping: In our fast, transactional world, we're called to ask what ancient wisdom seeks preservation through our hands, following the example of those who secretly maintained sacred traditions through persecution.

Experiential Teaching: Forest grandfathers don't lecture but create conditions where humans discover natural laws through their own choices and consequences—a patient approach we can apply when guiding others through frustrating situations.

Fungal Partnership: As Yasmine Ostendorf Rodriguez suggests in her book “Let’s Become Fungal!” to "Develop a relationship with your fungal alter ego and things will start to change. The more you work with them, the more they require you to change."

Mycological Toolkit

Join A Mushroom Hike: Challenge yourself to go on your first mushroom foraging expedition this fall, possibly with Mycoverse or local mycological societies. Experience firsthand the patient observation skills that traditional foragers developed over generations.

Cultural Research Project: Investigate indigenous mushroom traditions from your own region or ancestry. Many cultures have forest spirit traditions and sacred relationships with fungi that were suppressed during colonization or modernization.

Visual Folklore Study: Collect images of mushrooms in folk art, children's books, and decorative objects from various cultures. Notice how different societies represent fungi—as symbols of magic, abundance, danger, or transformation.

As we rediscover these ancient relationships between humans and fungi, we encounter more than botanical knowledge—we find sophisticated frameworks for ethical interaction with the natural world. The Старичок-Боровичок and his kin represent thousands of years of accumulated wisdom about reciprocity, respect, and the patient teaching methods of the more-than-human world.

My journey with Mycoverse has taught me that this wisdom refuses to disappear entirely, waiting instead for humans ready to approach the forest with appropriate reverence. After spending a year learning from Aaron Tupac's thoughtfully curated community, I feel I'm closing a gap with something that was meant to be part of me all along.

In our current moment of ecological crisis and cultural disconnection, these forest grandfathers offer guidance that extends far beyond mushroom foraging. They remind us that sustainable relationships with nature require humility, patience, and the willingness to be taught by forces greater and older than human civilization.

Events

Ready to dive deeper? Join our community of master artisans, cultural stewards, and creative practitioners exploring the intersection of traditional craft and contemporary life. Classes, intensives, and ceremonial gatherings across LA and online for artists, designers, crafters, illustrators, and makers of all backgrounds and levels. Our programs unite ancient wisdom with contemporary practice, cultivating living heritage through embodied craft, storytelling through making, communion with nature, cultural preservation, meditative practice, and the celebration of life's luminous beauty.

#russianfolklore #mushroomwisdom #forestspirits #slavicmythology #siberianshamanism #indigenousknowledge #borovichok #traditionalecology #culturalrevival #mycologicalwisdom #forestgrandfathers #shamanicculture #mushroomfolklore #ancestralwisdom #flyagaric #taigawisdom #folkecology #spiritualmycology #culturaltransmission #wildharvesting